I’ve witnessed a lot of patriotism and many patriots in the past few years, but nothing like my visits to Philadelphia, Gettysburg, and finally completing my journey in the nation’s capital—peering out on the mighty Potomac River on Veterans Day. Truth be told, I don’t find too much patriotism in my line of work. It seems it is a phenomenon of the living, not the dead.

I’ve witnessed a lot of patriotism and many patriots in the past few years, but nothing like my visits to Philadelphia, Gettysburg, and finally completing my journey in the nation’s capital—peering out on the mighty Potomac River on Veterans Day. Truth be told, I don’t find too much patriotism in my line of work. It seems it is a phenomenon of the living, not the dead.

The annual ghost trip I take, to some of the most haunted places in America—on Halloween—really surprised me this visit. Of course, I had some expectations and preconceived notions of what I would experience on the battlefields where the Civil War was won and lost. Or at the Liberty Bell, where a sound rang out, heralding the changing course of a land and its people, forever. As it turned out, I was fiercely-schooled by Great Spirit—challenging every drop of patriotism I’d walked in with. The piercing blade of the sword of truth is always shocking as it grazes the skin—Katy bar the door. (watch out—trouble is a comin’)

While patriotism can be a positive affirmation of life and cause, it can only be that if the foundation of those lives and causes are clean and unhindered by fear; for terror is the agent of illusion in all of us. Unlike the dead, the fascinations that inspire horror in the living are often gravely palpable—it’s easy to consider irrevocable actions when you are wearily-desperate.

As an empath, I have avoided places like Gettysburg, PA like the plague. Mainly because of the murderous roots and ill-gotten fruit that litters the birth of America and the distinguishing pain that lingers in the ethers. The ghosts of America’s past live everywhere. In some places, especially strong are the ways and means of colonialism and the detriment it has caused to the first nations, the land, and the well-intended or predatory folk who migrated here with the dream of creating a home where they could be themselves—while stealing that privilege from others .

- Battlefields

Don’t get me wrong, I am grateful to live in this country with all that it is and the freedoms it supports, but if we are to fulfill the original dream we must be willing to reconcile the trauma of the past and cherish that the true pursuit of freedom is liberating ourselves from fear, lack, and spiritual confusion.

These are the thoughts that meandered through my mind as I hovered 38,000 feet above the Earth, en-route to what would certainly be the opportunity of a lifetime—confessing those spirits in need of absolution and catharsis. You see, this is why disembodied spirits get stuck in the ethers of our reality long after their shell is gone. Often they leave the planet unprepared to reconcile all the life they’ve lived or the trauma and conflict of the burdens they bore—never revealing their true heart to another soul until death befalls them.

Lofty as my sky-time ideas were, from my experience, what seems so clear with 38,000 feet of perspective, will blur again into the needs, fears, desires, and illusions of the many beings that share this planet—and the many spiritual dimensions that surround her. Here is an accounting of my wayward haunted-journey with a dear friend, Stephen, in tow.

The Fallen Tree Inn- Carlisle, Pennsylvania

https://www.fallentreefarm.com

- Fallen Tree Farm

- Every Inn Needs a Porch

- Creeping in to creaky Inn

- Graham’s Retreat

- Tap, tap,tap…

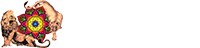

The Fallen Tree and The Brickhouse are two of the most haunted Inns in America—you can feel layer after layer of the faith and treachery that has crossed their paths. Every year I travel to some of the world’s most deeply-haunted lands and spaces for the purpose of learning the untold stories of the spirits that still reside within them. This year I went to Pennsylvania, the lands where some of my biological ancestors made roots in this country. I’d expected to connect with some of my bio-peeps but, as always, I let the Great Spirit guide my journey of telling the true accounts of the voices yet to be heard.

By the time we arrived in Carlisle, it was dark and almost everything was closed. We barely beat the clock to a hot meal at a local pub before checking in at the Fallen Tree Inn. The door was left open with the keys in our room, but trying to quietly enter into a home built in the early 1700’s just isn’t possible—they creak and shutter out of obligation.

So, a raucous entry we made, settling into “Graham’s Retreat” for the night. As tired as we both were from our long day of travel, neither Stephen nor I could sleep, the two of us giggling in the dark like siblings defying a parents request. He on the roll-away and me in the four-poster halfway across the room couldn’t deny the tapping, tapping, tapping on the window.

“What is that tapping in this godforsaken place?!” Exclaimed Stephen, and we both burst out in laughter.

Clearly, I’d done an insufficient job in preparing Stephen for what it’s like to go on a haunted trip with me, but in his defense; the tapping was getting out of hand. Thank-you, I said to the tapper, and whoever you are, we’d love to speak with you in the morning, preferably after coffee. Good night.

Early to rise was the Inn keeper and owner of the Fallen Tree Farm, she was absolutely delightful, as was the coffee she served. At the breakfast table some interesting conversation came to light. Haunting is a normal, comfortable idea for me and sometimes I forget, as when I asked her if she thought the Fallen Tree was haunted, to which she replied without a beat or a breath,

“Oh, definitely not.”

Hmmm, I thought, as I watched the entourage of spirits following her around the place. No matter, out-of-the-blue, our breakfast conversation turned to an important haunting of Pennsylvania—the Carlisle Barracks Cemetery. The site of the former Carlisle Indian Industrial School, where upwards of two-hundred Native children died, stolen from their tribal homes from 1879-1918. Stephen and I agreed this would be our next stop.

We headed back to pack for our next adventure, when the tapping began again in a room just up a short flight of stairs from us. It was the room “Coyle’s Hideaway” that was calling. Stephen entered with some reluctance, and I bumbled in, still weary from the slim nights sleep.

“Do you see the shadow in the corner of the room?” Asked Stephen.

“I do.” I replied. “How this works is, if you see the spirit first; you become its storyteller.” To which, he grimaced.

Reluctantly, Stephen asked, “Okay, what do I do?”

“Just go sit in the space, close your eyes and focus. Ask who is getting our attention and what they’d like to tell us.” I instructed.

“Oh my, he says his name is Jonathan Rickshaw! I thought you were kidding about talking to them.”

“You’re doing great! Keep going. Now ask him why he’s here in this room or on this land.” I encouraged.

“Okay…he says, at one time he’d invested in the Fallen Tree Farm many years ago (1840’s) and had a falling-out with the owner’s, losing his money. He died in the Shawnee Creek, somewhere in between Carlisle and Dover. I almost think he’s implying he was murdered. Is any of this for real?” Stephen said in dismay.

“Why wouldn’t it be? This poor guy has been looking to tell his story for awhile now.” I reassured. “Ask him if he’s ready to move on from this land.”

“Nope, but I am. Let’s go!”

I chuckled, “You did great, Stephen.” And, straight out the door we went.

- Graham’s Retreat

- Breakfast Room at the Fallen Tree

- Jonathan Rickshaw calling

- The ghost of J. Richshaw

- Stephen “Medium” MIller

The Great Spirit’s Children Always Come Home

As we drove to the Carlisle Barracks Cemetery, I pondered on all who had lost their lives on these lands; they felt so deceivingly peaceful on this crisp fall morning. Soon, we arrived and found that they’ve closed-off public access to the grave-site, which is now operated by the United States War College. The amount of visitors and the mounting public shame about the Carlisle Indian Industrial School history is no longer going unnoticed—much press has been given to the multiple native families asking for the remains of their children who were taken, and not returned home. Over 10,000 Rosebud Sioux, Northern Arapaho, Blackfeet Nation, Oglala Sioux, and Standing Rock Sioux children (to name a few), suffered because of the kidnapping, forced education, and harsh conditions of the school.

“…It immersed native children in the dominant white culture, seeking to cleanse their “savage nature” by erasing their names, language, dress, customs, religions, and family ties. The Carlisle goal: “Kill the Indian, save the man….”[1]

As we pulled up alongside the weather-weary section of white granite gravestones, we had to keep an eye out for the authorities. I sat quietly next to the 180 gravestones, wishing not to be interrupted by any living human. I began to pray, with, for and about the children who perished on this land, and a vision came; a bleeding human heart—it was still beating. Hmmm, I thought, A bleeding heart still beats; indeed it does. There was nothing left to say. I left an offering at the gravesites to honor the children, just as a security vehicle began slowing down.

“No worries officer, we’re on our way.”

Now onto The Gettystown Inn–Dobbin House and the battlefields of Gettysburg.

The Gettystown Inn–Dobbin House

- Meade’s Room

- Meade’s Room Interior

- Colonial Dining Room

- The Meat and Potato’s Were Haunting

- Old Kitchen Firebox

Not surprisingly, the energy of Gettysburg was very calm, even stoic. The land was beautiful and the folks at Gettystown were just as bright. Originally, a home built of wood and stone in 1776, by Reverend Alexander Dobbin, is rich in history and spiritual imprints of all that occurred on the land it was built. A stop on the Underground Railroad—they’ve preserved the hideout built in between floors; it was hidden in the midst of the many rooms currently housing the colonial eatery and tavern.

Not surprisingly, the energy of Gettysburg was very calm, even stoic. The land was beautiful and the folks at Gettystown were just as bright. Originally, a home built of wood and stone in 1776, by Reverend Alexander Dobbin, is rich in history and spiritual imprints of all that occurred on the land it was built. A stop on the Underground Railroad—they’ve preserved the hideout built in between floors; it was hidden in the midst of the many rooms currently housing the colonial eatery and tavern.

Gettysburg is a town tall on history but seemingly short on hauntings, I was a little disappointed. However, to towns which have housed the greatest tragedies—the greatest focus to heal souls is drawn. I’d half expected to find it like the “Walking Dead”, but on some level was pleasantly surprised it was not. In Gettysburg, it seems the dead have been delivered but the living are the ones who suffer.

The Impact of War

As we traveled around the many Civil War battlefields: Knoxlyn Ridge, Wheatfield, Culp’s Hill, and the protective boulders of the Round Tops, to name a few; I found it all very peaceful. Not a ghost to be found from the era. Certainly, there were many imprints that would speak to you if your energy was aligned with them, but what was interesting were the live humans. I witnessed more than a few people walking the streets near Cemetery Hill and the Wheatfield that seemed to be having angry conversations with themselves while they

whittled away the miles. I was curious if they were locals, everyone I saw seemed to be quite familiar with the terrain.

whittled away the miles. I was curious if they were locals, everyone I saw seemed to be quite familiar with the terrain.

Dinner and the next days breakfast were hearty, and brought me back to a past-life memory of churning my own butter, and making cheese. The huge ten-foot fire-boxes found in the kitchens, built separately from the rest of the home—just in case they burned. I don’t know if I prefer the simplicity of the era or the immediate gratification of our modern times. What I do know? Is the internal-tyranny created in the minds of those who struggle to overcome the effects of war—is the only unwitting victor.

The Brickhouse Inn, Gettysburg, PA

- Brickhouse Inn

- Doesn’t look scary from the outside.

- Halloween Guided Tour with Nick

- Just a Doll in a Hall

- Battlefields

We were now on the final night of our adventure. In downtown Gettysburg—at the historic Welty House. It was built in 1838 and originally housed Confederate soldiers and was a snipers roost during the Battle of Gettysburg. The other building that is a part of The Brickhouse Inn is a beautifully restored 1898 Victorian mansion, where we sat for breakfast at a communal table and chatted with a Civil War enthusiast in town for a reenactment.

I’d awoken at five a.m., long before coffee was to be served; when, finally, I found the last ghost left in Gettysburg. I was walking to my car, headed to the Starbuck’s down the street, when I heard a voice. It was still dark and I cautiously looked behind me as I adjusted the keys in my hand to a defensive position, in case of attack—but there was nothing and no one.

As I climbed into the car to drive, the spirit appeared right next to me in the passenger seat. Missing one leg, this tall young man with blonde hair tucked under his dark colored forage cap, said hello—he’d been around the age of twenty-three when he died. A gentle man and seemingly still lost in the war zone, but quick with a quip or two; he made fun of me as I passed through the drive-thru for my coffee. I too, struggle with what to consider as progress, I told him. His surname was Robeson, and he was cordial for the rest of the drive, I thanked him for his service—he disappeared from this dimension as quickly as he had arrived.

As I climbed into the car to drive, the spirit appeared right next to me in the passenger seat. Missing one leg, this tall young man with blonde hair tucked under his dark colored forage cap, said hello—he’d been around the age of twenty-three when he died. A gentle man and seemingly still lost in the war zone, but quick with a quip or two; he made fun of me as I passed through the drive-thru for my coffee. I too, struggle with what to consider as progress, I told him. His surname was Robeson, and he was cordial for the rest of the drive, I thanked him for his service—he disappeared from this dimension as quickly as he had arrived.

I considered his visitation, a sort of pity-sighting—he popped in to let me know there were a few of them left, and no-doubt; to keep alive the truths of his time.

Now my trip was complete. We headed back to Philly, and made it in record time. From all I gleaned, the longest standing haunting in Pennsylvania is the government’s refusal to legally acknowledge any indigenous tribe in the state. A pattern of pain that will continue, not only in the federal court system (as it has since the 70’s) but in the court of public opinion, until it can finally be resolved to support the freedoms every one of the Creators creations, has the right to.

Special thanks to Stephen Miller for some fine photography.

[1] ‘Those kids never got to go home’ By Jeff Gammage / Staff Writer The Philadelphia Inquirer, Sunday, March 13, 2016